TEXT REVIEWED

Stephan Schlak

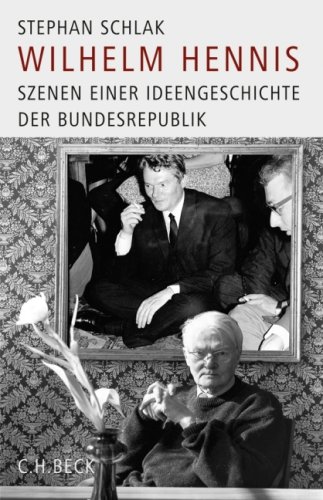

Wilhelm Hennis.

Szenen einer Ideengeschichte der Bundesrepublik

C. H. Beck Verlag, Munich 2008 pp. 275 + index

Dated…or contemporary?

Wilhelm Hennis is a radical in the early nineteenth-century sense whose political and intellectual passions predate conceptions of left and right, socialist, liberal and conservative, conceptions that remain stamped on our political culture. His insistence on the importance of a political culture reaching back to Aristotle and Plato made him seem out of time to his more ‘progressive’ contemporaries during the 1970s; but as Schlak argues, it is the arguments of those former progressives that now seem very dated, and those of Hennis both prescient and contemporary.

Born in 1923, he lived out the early years of the Third Reich in Venezuela; called up into the navy he survived three sinkings and a pending court martial to begin his life again shortly after the war in Göttingen as a student of law. A member of Schumacher’s SPD, he learned about political process as a Bundestag assistant to Adolf Arnd, legal adviser to the party. In 1953 he became assistant to Carlo Schmid in Frankfurt, but as he writes in his self-portrait, he ‘steered clear of the Frankfurt Institute’. By the early 1960s he was a full Professor in Hamburg so popular with his students that in 1966 they sought to keep him in Hamburg by staging a demonstration (photo p 145).

But this quickly changed. Two pages later we have a photo taken in Freiburg in 1968 of a cycle rack behind which has been sprayed ‘Haut dem Hennis auf den Penis’ (p 147). On the same page there is an account of how, with yet another exam for politics students disrupted by protesters, his fellow Professor called the police; on whose appearance, Hennis observed, the greater part of the protesters fled into the Sociology Seminar.

During much of the 1970s Hennis was a harsh and polemical critic of self-styled radicals, a stance which also brought with it a clear distancing from Jürgen Habermas, whose Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit he had originally published in his book series Politica. As Schlak argues, Hennis’s early stance as a proponent of institutional reform in the Bundesrepublik and ‘curator’ of its leading political concepts – he was originally engaged by Werner Conze to write the entries ‘Öffentlichkeit’, ‘Politik’ and ‘Moral’ for Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe (p 64) – switched in 1968–69 to that of a vehement critic of the reshaping of political language in the 1970s in terms of ‘movement’ and ‘change’ (p 156).

Rediscovering Max Weber

He had already in 1957 published an essay arguing that what ‘public opinion’ surveys collated were private opinions, and that this elision involved a category mistake that failed to distinguish the political public realm from the private domain (a basic insight that eludes modern politicians). During the 1970s he relentlessly criticised the manner in which this elision was extended into conceptions of democracy and legitimacy, arguing that the overblown rhetoric of the student movement threatened to bring about the very destabilisation of political order that they believed had already occurred. This made Hennis very unpopular with those born in the 1950s and whose principal life experience was of the boredom and security of family life.

The ‘German unrest’ which Hennis had first documented in 1968–69 culminated in the autumn of 1977 with the Mogadishu hijacking, the murder of Hans-Martin Schleyer, and the collective suicide of Rote Armee Fraktion terrorists in Stammheim prison. Hennis flew to New York to take up a Visiting Professorship at the New School the night the police found Schleyer’s corpse, and he was thereby liberated from the polemical and overheated ‘deutsche Herbst’. Importantly, Hennis came into contact in New York with Hans Staudinger, one-time student of Max Weber, and in conversations with him rediscovered a connection to Weber that had been broken by his American reception.

Hennis had first encountered Weber in 1944 when he read Jaspers’ Max Weber. However, on his visit to the United States in 1952 he had personally encountered two variant versions of Max Weber’s heritage: that of Talcott Parsons, and that of Leo Strauss. Both Parsons and Strauss believed that Weber stood for ‘value neutrality’, but the former thought this a good thing and the latter a bad thing.

Since Hennis also took a strong dislike to Parsons’ fashioning of Weber as a sociologist, Strauss’s view tended to prevail, such that during the 1950s and 1960s his view of Weber was not so very different to that of Habermas and Mommsen, for example. Detached from German politics in New York, however, Hennis found a way back to the interest that had originally been fired by his reading of Jaspers, seeking a theme in the work that made sense in terms of the Aristotelian political tradition which he had sought to uphold in the polemical debates of the 1970s.

The scholarly outsider

Having disabused himself of the idea that Weber was some kind of value-neutral sociologist, he discovered in Weber’s efforts to clarify what he had sought to argue in the Protestant Ethic – the ‘Anti-Kritik’ – the red thread that ran through Weber’s work – the anthropological concept of Lebensführung. This was the key Fragestellung that he presented in the first of many essays on Weber; and I count myself very fortunate to have met Wilhelm Hennis in the autumn of 1982, having been shown a copy of the typescript by Pasquale Pasquino while we were both working in Göttingen University Library. At the time I was translations editor of Economy and Society, which had a policy of publishing one translated article per issue, and so this first article appeared in English the following spring, within a year of its first publication in German.

This turned out to be the first of many essays that established a major turning point in our modern understanding of Max Weber, wresting him out of the clutches of system builders and sociologists and replacing him in a classical tradition of political thought which comprehended the social and the economic – the category of Politica, the book classification that Hennis had first encountered as a student in Göttingen University Library, and which had prompted the work on his Habilitation, Politik als praktische Philosophie. This must have been a source of some irritation to some of the editors of the Gesamtausgabe, whose ponderous approach to editorial work was duly slated by Hennis in his article ‘Im langen Schatten einer Edition’, first appearing in FAZ in September 1984 and then extended in the Zeitschrift für Politik for June 1985.

The combative style Hennis brought to the established Weber reception and which placed him in the position of the scholarly outsider whose authority was, however reluctantly, recognised by all the insiders was a familiar stance, as Schlak notes. At the same time that Hennis was opening up Weber to new generations of students and scholars he was also conducting a vigorous campaign against the degeneration of party and politics in the Kohl era which among other things involved much correspondence with the German President. More recently of course he instigated a highly successful public write-in to the Attorney-General’s office in connection with the destruction of state papers on the part of members of the outgoing Kohl government.

Schlak organises his biography as Scenes from a History of Ideas of the Federal Republic, hinged on the manner in which Hennis has always understood political science to be a practical activity, a science of politics in a classical sense which involves both vigorous engagement with the constitutional matters of the day, as well as reflection on the instrumentarium that the scholar brings to the practical world of politics. And this is also an account of an engagement with a public domain in the proper sense of the word – there is virtually nothing here of Hennis the private person, and none at all of Hennis the family man or loyal and generous friend to, now, several generations of scholars and students. Schlak was born in 1974, the year before Hennis’s showdown with Jürgen Habermas over the problem of ‘legitimacy’ at the annual conference of the German Political Science Association; he has no axe to grind from those years, and brings an entirely fresh and not at all uncritical perspective upon the long life of Wilhelm Hennis as a ‘public intellectual’ in the very truest sense of the term.

Keith Tribe, The King’s School, Worcester

Keith Tribe is a professional translator, private scholar, professional rowing coach at The King’s School, Worcester and Senior Visiting Fellow in Intellectual History at the University of Sussex.

Under the supervision of Maurice Dobb 1973–76 he wrote a thesis on agrarian capitalism and classical economics, and was appointed Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Keele in 1976. In 1979 he received a fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation to study German economics, from 1979–80 in Heidelberg and then from 1982–84 at the Max Planck Institut für Geschichte, Göttingen. During this period he began to translate the work of Wilhelm Hennis on Max Weber, and in 1986 he completed his study of German Cameralism, Governing Economy (CUP, 1988). In the meantime he transferred to the Department of Economics at Keele, where he taught mainstream undergraduate economics until his retirement as Reader in 2002.

His major project on the invention of the discipline of economics will be published under the title Making Economics. The Formation of Economic Science and the British University 1805-1950 (Brill, 2009). In 2009 he will also publish his translation of Wilhelm Hennis, Politics as a Practical Science (Palgrave) and a new translation of Weber’s Economy and Society Chs 1–4 (Routledge).