from Chapter One

Entering the Secret Garden

Bertrand Russell recorded that as an undergraduate at Trinity College, Cambridge, ‘I was persuaded that the dons were a wholly unnecessary part of the university. I derived no benefits from lectures, and I made a vow to myself that when in due course I became a lecturer, I would not suppose that lecturing did any good.’ However, he then admits that on moving from being a student to being a Fellow of the college, a sharp change in optic took place: ‘While I was an undergraduate, I had regarded all these men as merely figures of fun, but when I became a Fellow and attended college meetings, I began to find that they were serious forces of evil.’ The particular issue Russell had in mind involved the Junior Dean of Trinity, who had to be got rid of after a scandal in which he had raped his own daughter. This occasioned a debate in the college meeting where the Master, speaking in alleviation, stressed most particularly how excellent the dean’s sermons had been.

My own experience, on becoming a Fellow of Magdalen, was rather different though it has to be said that anyone who sat through enough college meetings in almost any Oxford college could imagine well enough the debate which had so shocked Russell. At Magdalen the Dean of Divinity did almost nothing and was rumoured to be an atheist. Certainly, the interest he took in the religious disposition of the students was less than cursory. A. J. P. Taylor’s proposal that the college Chapel be turned into a swimming pool had not gone through, but I sometimes wondered if more Fellows might have gone near the Chapel had he succeeded. The closest thing I had to a religious experience as a young Fellow, on being admitted, was provided by the legendary Tallboys, a college servant then in his nineties. Traditionally, in the days before there were pensions, the college had allowed its servants to work as long as they wished. Tallboys, a wizened little pixie of a man, was far beyond doing any actual work but he hung around the Chapel in the general capacity of a verger. Tallboys, inevitably, was a repository of college lore and traditions, for he had been around the place for nearly 80 years. As such he was treated with a certain respect.

The bells in Magdalen’s Great Tower are rung for each new Fellow on admission and again when he dies. I was only 26 when elected, by some margin the youngest Fellow in the college, and it was a fairly overpowering experience to hear the great bells tolling out, over and over, all for me. I stood in the front quad listening, wishing my mother and father could have been there to hear it. Tallboys emerged from the Chapel and, seeing me, advanced towards me, smiling broadly. ‘You might as well enjoy it now, sir,’ he said, beginning to laugh, his pinched shoulders shaking almost uncontrollably, ‘because the next time it rings for you, sir, you won’t be hearing it. Because, sir, you will be dead.’ With which he gave a high-pitched cackle, greatly pleased with his own remark, and scuttled away like a withered crab. It was straight out of Gormenghast or a Hammer horror film.

I thought of my parents because their paths had been very different. My father had run away from home after violent quarrels with his father,

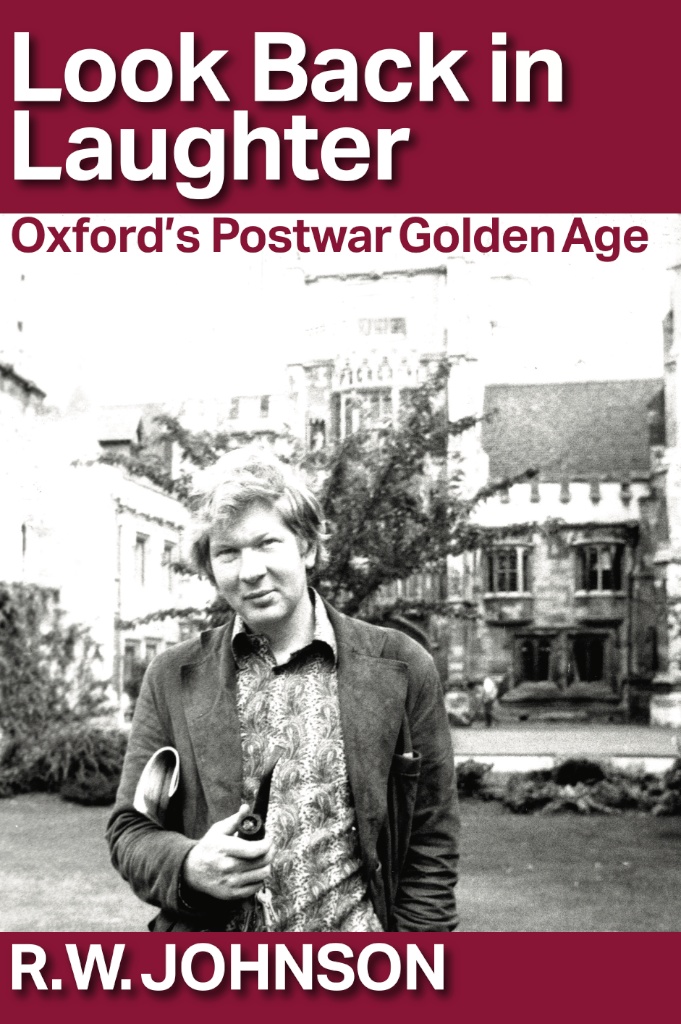

Plate 5 (right ) The author arriving in Oxford from Natal in October 1964 in the only suit he then owned. (Rhodes House Archives )

My mother, the seventh child of a railway-engine driver, was the only daughter in her family not to go into domestic service, instead leaving school at 14 to work in Boots the chemist. My parents were poor – they had never owned a house and such money as they had went mainly on their six children – but they loved reading, something they passed on to me. What was not passed on to me was religion, for despite an unhappy interlude as an altar boy I soon escaped into happy atheism. My many uncles and aunts were all straightforward working-class folk and I was the first person even in our wider extended family to acquire a university education. I could not be unaware that such a background and my state schooling was highly atypical of the men who were now my Magdalen colleagues, most of whom had been to private schools and who were almost invariably more affluent than me. Even when I had first arrived in Oxford I had been struck by the ease with which my more upper-class peers accepted the normalcy of having domestic servants (‘scouts’) to make their beds and clean their rooms. For someone whose aunts had all been domestic servants, this took some getting used to.

It was just five years since I’d first arrived at Magdalen as a student and inevitably my mind drifted back to that. My overwhelming impression had been of the college’s majestic buildings and its sheer spaciousness, for Magdalen not only has its own large Deer Park but the college is set in its own spreading parkland. The college had slowly grown from the old Grammar Hall (the only building now dating back to its foundation in 1458) and its central Cloisters to comprehend a magnificent Georgian block known as New Buildings and then several later quads as the college expanded in the 20th century, but each of these additions had been built of stone consonant with the original buildings and they too have been widely spaced. Everywhere were great spreading green lawns and gardens, opening into the circular walk known as Addison’s Walk (the poet and essayist Addison, a Fellow of the college, was wont to walk there) and then on into the Fellows’ Garden, winding along the river until one reached the college’s playing fields. It was utterly, stoppingly beautiful and a very English beauty at that, quite different from the lush beauty of sub-tropical Durban that I was used to. Above all of these loomed the Great Tower, a building so distinctive that it was often used on posters to symbolize Oxford or even England – Charles I described it as ‘the most absolute building in England’. All the life of the teeming little village that is Magdalen is lived under the shadow of this mighty tower, whose construction was begun in 1492 just as Columbus set sail, a fact at which American students would simply shake their heads.

Living amidst these ancient buildings, replete with battlements, arrow-slits and gargoyles, and spreading parks and lawns, had an enormous effect upon us. The college had been there since time immemorial and its peaceful order spoke of a settled community of high intellectual distinction. It had not only been there, overpoweringly, further back than one could easily imagine but it was clearly there forever, just as much as the River Cherwell or the Cotswold hills. It was by far the biggest and most beautiful of all the Oxford colleges, with the possible exception of Christ Church, though so much of Christ Church’s grounds were in effect a public park that it didn’t seem to count. To be a student at Magdalen meant to be reminded daily, even hourly, what an awesome foundation it was and to a considerable extent this affected the awe in which we held the Fellows of the college. It goes without saying that we assumed they were all men of great learning and the sort of razor-sharp brains that made one quail, but it was more than that. The majesty of the surroundings meant that we could not imagine a higher form of intellectual authority than to be a Fellow of Magdalen, so we didn’t just assume the dons were clever but that they were great men. Students hung on their words and would tell one another with delight of the brilliant aperçus or witty jokes they had heard from their tutors. In this way one learnt the first names of dons, their foibles and their fame. Although we all lived on staircases and got to know our staircase companions best, this nonetheless meant there was a spreading sense of community, one we were proud to belong to.

It took some time after my first arrival to realise how profoundly that physical geography of Magdalen has moulded the community it shelters. For the college’s unusually spacious and spread-out nature encouraged a variety of cliques rather than the more cohesive communities found in more tightly packed colleges. The concomitant virtue was a strong sense of live and let live. One of the sights of Magdalen in that era was Richard Collins describing vast ballet leaps and pirouettes across the lawns of St Swithun’s quad. He was an unambiguously gay figure – even his ordinary walk was a camp swagger – always wearing a crimson silk sash, jeans and pullover which looked as if they had been sprayed on. His father was the left-wing cleric, Canon Collins, a man both of passionate causes and an eye to the main chance. Like all the canon’s four sons Richard had been to Eton – no point asking how that had been done on a canon’s salary – which no doubt explained the enormous sense of social self-confidence which enabled him to get away with such exhibitionism. Visitors from other colleges, catching sight of his pirouetting figure, crimson sash held aloft, would gawp and ask, ‘Were Magdalen’s hearties really prepared to put up with that?’ It made you realise that either Magdalen had no hearties – it seemed, instead, to be full of literary and theatrical types – or that if they existed they too were bound by the prevailing air of laissez-faire. The one thing that was unimaginable was that anyone would seek to interfere with whatever Richard Collins or anyone else might choose to do. It was the most tolerant atmosphere I had ever experienced in my life.

One result was that all manner of camp humour and behaviour flourished. This was all long before the era in which gays ‘came out’ and it was startling for someone as conventional as me to hear the wild whoops and squeals of effeminate affectation which generally accompanied this manner of ‘camping it up’. Chief among such characters was Roger Williamson who loved to affect a self-parodying loucheness, calling everyone ‘my dear,’ and who simultaneously mocked and adored the social habits of the upper classes. Roger’s natural set was that of Etonians and other public schoolboys who had invariably become acquainted with homosexuality at school and who, accordingly, were unshocked by his campery; indeed, not a few of them (like Roger) did turn out to be gay. Roger was, in any case, keen to befriend Etonians since his great wish in life was to teach at Eton. At the same time he would study their habits, accents and assumptions with an anthropologist’s passion: ‘Don’t you absolutely love the way they think the world is almost exclusively made up of people like themselves? I can’t get over it.’ Rupert asked me if I had a sister and simply assumed she was a deb who would soon be ‘coming out’. Roger, whose social antecedents were actually several rungs below that, was well aware that the somewhat squarer grammar schoolboys would doubtless jib a little at his camp style, and he would quickly retreat into a sort of theatrical upper-classness. ‘Hmmm. N.O.C.D., I’m afraid, my dear,’ he would say pettishly as he pulled back. N.O.C.D. meant Not Our Class, Dear. Similarly, he affected a dismissive horror of ‘the Hets’ (heterosexuals). In my mind I tended to conflate Roger with Anthony Blanche in Brideshead Revisited and I am sure I was not the only one to do so. It was a comparison which, almost certainly, Roger would have greeted with a knowing scowl and hoots of laughter.

Roger’s frequently outrageous flights of humour would doubtless have got him into trouble in almost any environment outside Magdalen. But Magdalen was in the strange position that its most famous alumnus, Oscar Wilde, had been hounded and ruined for his homosexuality. The elegance of Wilde’s wit always contrasted with the sheer brutishness of his unfair treatment: it was as if one of the delicate college deer were to be torn to pieces by a hulking great Rottweiler. Oscar had always talked of his time at Magdalen as ‘the most flower-like time of my life’ and even several generations later there was something about his elegance, wit and sophistication which went very near the heart of the Magdalen spirit. Magdalen was still proud to call Oscar one of its own and the very thought of the sheer illiberality of his fate was sufficiently hateful as to guarantee a sort of maximum permissiveness. What I only later learnt from Old Members (as former students of the college were called) was that Roger might have fitted almost unnoticed into the Magdalen of an earlier period when the all-male undergraduates often wore make-up, walked hand in hand and there was a horror of any contact with women. Some of the older scouts talked of similar things and of how strong freemasonry had simultaneously been among the Fellows. ‘It was all buckled shoes, powder puffs and masonic signs,’ my scout told me matter-of-factly, as if he expected that I might adopt some of these habits too.

Roger’s greatest pleasure was to go, with a suitable companion, to see good ballet or opera in London. This meant a late return to Oxford on the last train, a miserable, slow-moving diesel which was always full of sullen townsfolk, displeased at being out of their beds, and on weekends a good smattering of football hooligans. If one had had to pick an audience likely to be maximally provoked by Roger’s campery, this was it – and I knew enough to know that a good ballet would leave Roger in a state of excited exultation, likely to bring out his most exuberant exhibitionism. One Monday I enquired how the ballet had been. ‘Divine. Absolutely to swoon for. I took Anthony along so it was all very nice till we got to the late-night diesel. Full of the most dreadful people. They hated us. Absolutely N.O.C.D.’ Anthony looked sheepish – ‘we nearly got lynched,’ he said. ‘Roger and I found something funny and began shrieking over it. People started coming over, offering to thump us if we didn’t shut up. But we couldn’t stop laughing. We only just got to Oxford in time.’

It turned out that Roger had found an abandoned Evening Standard on the train with the headline PASSENGERS PANIC AS SHEIKHS CLASH IN MID-AIR. The story concerned a sheikh from a Middle Eastern state who had decided to bring his entire harem to London. Although wearing veils and the regulation shapeless dresses, the women were clearly very attractive and a neighbouring sheikh, also on the plane, had begun to flirt with one of them. The enraged husband had drawn a scimitar while the flirtatious sheikh had armed himself likewise whereupon, to the great alarm of other passengers, a sword fight worthy of an early Hollywood epic had ensued. Roger, greatly taken with this and already extremely conscious of the menacing and homophobic mood of some of their fellow passengers, had challenged Anthony to come up with a headline depicting their own situation. What had emerged, amidst shrieks of delight from Roger, was HETS PANIC AS OXFORD QUEENS CLASH IN DIESEL. Roger, as it turned out, was to get his wish and later became a teacher at Eton but soon turned up with his arm in a cast. His gay manner had quickly infuriated the hearties and a group of senior boys had thrown him in a fountain, breaking his arm. The headmaster, Anthony Chevenix-Trench, ultimately demanded Roger’s resignation, promising that in return he would write him good references for whatever jobs he then applied for. Roger resigned and Chevenix-Trench double-crossed him and wrote him filthy references. This was apparently the standard gambit in such cases at English private schools of the day.

Perhaps Magdalen’s permissiveness had not been altogether kind to Roger: Eton was not Magdalen, and nor was the rest of the world. Again, one could not but think of Anthony Blanche but in Brideshead Revisited the sexually ambiguous Blanche is attacked by the hearties while still in college, led by the oafish Boy Mulcaster, debagged and thrown in a fountain. Such behaviour could not conceivably have taken place in Magdalen. But then Blanche, Charles Ryder and Sebastian Flyte were all at Hertford College (Evelyn Waugh’s own college) and Hertford too is not Magdalen. There was a strong belief at Magdalen that Waugh had really based his Brideshead characters on Magdalen rather than his own college and occasionally undergraduates would enjoy playing up to the Brideshead image: one undergraduate I knew made a point of flying to Paris each term to get his hair cut. Similarly, I was told by one of his contemporaries how the young Kenneth Tynan had arrived in the Lodge accompanied by suitcases and a large trunk which one of the porters helpfully loaded onto a trolley. ‘H-h-h-have a c-c-care, my g-g-good man,’ Tynan expostulated, ‘That trunk is f-f-f-freighted with silk shirts.’ But there is some danger that I will give the impression that Magdalen’s hyper-tolerance encouraged an atmosphere which was all loucheness and preciousness. This was not so and nor was there any sense of easy intimacy. The atmosphere was not subject to any form of discipline but it was nonetheless taut with a feeling of high intellectual expectation. The Fellows were regarded with some awe as men of unexampled erudition and most students took their work extremely seriously. People often kept to themselves, spending long hours of study in their own rooms and treated one another with a degree of polite formality. The overall result was a community which, though wholly un-policed and completely tolerant of any form of dissent or eccentricity, was nonetheless self-disciplined, studious and light-hearted. It was a strangely perfect mix which seemed to defy everything Aristotle had said about the grave difficulties of governing men, for here there was no government, no discipline and everything was permitted, yet everyone worked and behaved.

from Chapter Three

Happy Days

In Brideshead Revisited Charles Ryder has rooms on the ground floor and one evening Sebastian Flyte’s head suddenly appears through the drawn curtains as he vomits violently into Charles’s room. Thus begins a beautiful friendship. My own introduction to Michael Deeny and John Sergeant was not dissimilar. I had ground-floor rooms in the corner of St Swithun’s Quad. On several evenings I had heard a loud, stammering Irish voice outside and recognised it as belonging to Deeny. Not that I knew him but his voice was as distinctive as his appearance. Which was saying quite a lot for he sported a silver cane and a long black opera cloak lined with scarlet silk and smoked exotic Turkish cigarettes. The combination was positively Wildean, which it was doubtless meant to be. This had not prevented quite a few of my neighbours who were dutifully studying at the time – it was around 11 pm – from angrily shouting at Deeny to be quiet and stop disturbing them. This he wholly ignored. On the evening in question I too was finding the loud Deeny stammer an irritant and, parting my curtains, put my head out to say so. ‘Arr, hullo,’ said Michael, ‘Although I hope you’re n-n-n-not g-g-going to agree with J-j-john.’ John Sergeant was standing grinning wearing a grey button-down reefer jacket. He nodded in friendly fashion. ‘I’m just trying to save Michael from himself,’ he said, his face lit up with laughter, looking somewhere between a cherub and a naughty choirboy.

‘Although, the thing is –,’ began Michael. He began almost every sentence with ‘Although,’ pronouncing it ‘Awwwwlthoooo’. It turned out that they had been at the Oxford Union, where they customarily ranged themselves on the Left. Michael, wholly unabashed by his stammer, had made a number of interventions and was irritated to find these drawing fire from his opponents, for whom he had little time. His bête noire was Douglas Hogg. When Hogg and others, using the parliamentary language and procedures of the Union to pour contempt on Michael’s speech, had irritated Michael sufficiently he had begun to hurl insults at them of which the most printable was ‘pederast’. This had earned him a caution for unparliamentary language so he had adopted a new tack. ‘The thing is,’ said John, ‘Michael has this idea that if he gets up and prefaces his remarks with the phrase “Although a hell of a mess as a human bein’ meself,” he can then accuse others of anything he likes, from bestiality to homosexual rape. I keep trying to tell him this is no defence against defamation suits.’ Michael smiled happily. ‘Although, it w-w-works very well. You s-s-should have s-s-seen Hogg’s f-f-face.’ Our conversation dissolved into laughter and before long my neighbours were irritably calling on me to be quiet too.

Michael and John became great friends whom I was always happy to see – invariably they had various jokes on the go and John was also a great mimic. They wandered around together most of every day. Michael was reading Modern History, though quite what time he ever found for academic work was, at best, unclear – he seemed gloriously unconcerned by it. Studious though I was myself, I could not but be fascinated by Michael’s magnificent disregard for all normal academic rules. John was reading PPE and was careful to do enough to get a reasonable degree but I felt closer to Michael. Instinctively, I recognised in him another colonial boy who had come from a country in which wild and absurd things were just as likely to happen as they were in South Africa. Like me, he was taking the measure of Oxford as a strange and different civilisation in the more orderly metropole, just as Oscar Wilde, also arriving from an Ireland in which preposterous things could always happen, had once done. I got into the habit of dropping into Michael’s rooms at about 11 am which meant one was in time to assist his leisurely levee at 12 or 12.30. Since lectures were given between 9 am and one o’clock, this timetable meant that Michael was never able to attend any lectures. Above his bed hung his treasured picture of ‘B’ Company – a dismal First World War photograph of a number of badly battered-looking men standing to attention on a misty parade ground with huge gaps between them, representing all the men who had been lost since they first assembled. No wonder the men looked so lugubrious – there were far more gaps than men. There was something undeniably comic as well as dreadfully sad about the picture.

Michael came from Lurgan in Northern Ireland and had been to a Jesuit school, Clongowes, in Eire for the Deenys were that rarity, comfortably off Northern Ireland Catholics. Michael told me many stories about this, most of them centring on his father, who was a doctor. During the war, he told me, Eire had considerably strengthened its army just in case; Dr Deeny was asked to assist. After two months the commanding officer came to him considerably disturbed. Large numbers of simple country boys had been enrolled and on entry they had had an almost nil rate of venereal disease. Now, after two months in proximity to Dublin’s fleshpots the rate had jumped to 40 per cent. It was agreed that Dr Deeny would give the entire company a rip-roaring speech on the dangers of venereal disease and that this would be made as blood-curdling as possible so as to strike fear into every heart. The company was assembled on the parade ground, ordered to stand at ease and then Dr Deeny let fly through a megaphone. It had, he said, come to his attention that some of the men were visiting houses of ill repute to consort with low women. He knew they were all country boys and that things like this hadn’t existed in the countryside but they were a part of life now. Contact with these low women had in turn led many of the men to contract venereal disease. He wished to draw their attention to what a horrific thing this disease was and how utterly imperative it was that they avoid it. He laid it on thick with many disgusting and painful details barked out through the megaphone. The list of symptoms got worse and worse and ended up, thunderously, with complete paralysis and insanity. Followed, even more thunderously, by death. All this was bellowed in staccato through the megaphone. The commanding officer was rapturous – ‘That was just what I wanted, well done’. But three months later the rate of venereal disease in the ranks had risen to 80 per cent. For what Dr Deeny had done was to draw the attention of the disease-free 60 per cent to the ready accessibility of houses of ill repute with low women in them. Moreover, as later interviews revealed, they were tremendously impressed that despite the horrors of venereal disease, so many within their own ranks clearly thought the fun they had in such milieux well worth the risk…

In those pre-civil rights days the sight of a prosperous Catholic professional like Dr Deeny going about his business was a provocation in itself in the eyes of Northern Ireland Protestants, rather as the sight of a successful black professional would have been a provocation to the good ole’ boys of any town in the pre-civil rights American South. So there was a great deal of muttering about the need to bring the Deenys down a peg or two to show them what was what. Naturally, such talk was a hot topic of conversation in the Protestant pubs of Lurgan where, as more and more drink was consumed on a Saturday night, the suggestion would be made that perhaps the best way of bringing Dr Deeny down a peg or two would be by lynching him. Finally, it was decided that this should take place on the following Saturday. So once the Protestant pubs reached closing time a large crowd of well-oiled citizens began pouring along the road to the Deenys’ house. But they had broadcast their intentions all too publicly and shortly before the house Dr Deeny was waiting for them with a line of young Catholic labourers, brought in from the countryside for the occasion, all armed and strung across the road. Dr Deeny ordered the crowd to stop, turn round and go home. Those in front had frozen at the sight of the guns but those behind, unable to see this, pushed forward strongly, eager to string up old man Deeny. The result was that those in the front line of the mob were unwillingly and slowly pushed forward, further and further. Dr Deeny, seeing this, ordered his men to shoot a volley over the heads of the mob. This they did but one young lad, petrified with fright, failed to lift his rifle and when the volley was loosed squeezed his trigger in sympathy, shooting straight into the crowd. In the front row a man keeled over, shot in the stomach. Pandemonium reigned and then the cry went up, ‘Now we’ve got him! Now Deeny can be tried for murder!’ and with that the body of the shot man was borne victoriously away.

Dr Deeny went on trial for murder though he paid little attention to the court proceedings and retained a secretary to whom he busily dictated a large business correspondence while the trial, which he was not disposed to recognize, went on around him. Meanwhile the injured man was still in hospital and every day his supporters would issue a fresh bulletin about how ‘this brave son of Ulster remains at death’s door thanks to the murderous efforts of Dr Deeny.’ This situation dragged on for some time until one of the older Deeny children returned from his university studies in England. Having been away a long time he was no longer easily recognized by locals, a fact he exploited by going for a beer in a Protestant pub. He found himself next to a young man who seemed to be trying to cram down as many beers as he could in the shortest possible time. When he asked him what was wrong the young man told him he had long been kept prisoner in hospital by a bunch of maniacs. He had only had a flesh wound which had healed some time ago but his captors were keen to keep him in hospital so that they could claim he was dying. As a result he hadn’t had a drink for six weeks. He had just managed to escape and was trying to slake his thirst as quickly as he could. Naturally this intelligence was fed back to Dr Deeny and the trial collapsed.

To say that Michael had a great fund of such stories seriously under-describes the situation. It was more that his life was lived as mere connecting intervals between funny stories. Indeed, since Michael evidently hadn’t come up to Oxford with the idea of wasting time on his studies, the whole point of his existence lay in amusement of one kind or another. Michael not only relished jokes and funny stories of all kinds but, when he did read a history book, would always come away with any ironic or amusing twist that it had, leaving its serious purpose to one side. I remember once one greyly serious fellow student of Michael’s indignantly demanding of him what he thought he was doing at Oxford. ‘I…er… although, I’m l-l-living a b-b-beautiful life, as we’re all s-s-supposed to l-l-live,’ he replied, adding with some asperity, ‘Although if you think y-y-you’re an a-a-adornment to my b-b-beautiful life, ye’re g-g-greatly m-m-mistaken.’

Michael’s liaison with John Sergeant was not just about having fun informally, for John was already regarded as one of the funniest men in Oxford and he and Michael often worked together in devising sketches and gags for the satirical revues John was active in. It was an era greatly influenced by the enormous success of Beyond the Fringe and the consequent satire boom, including the emergence of Private Eye in 1961, echoes which were particularly strong at Magdalen where Dudley Moore had been an organ scholar not long before and Alan Bennett a young history lecturer. John was already quite prominent in the world of Oxford revue and theatre alongside Michael Palin, Diana Quick, Tammy Ustinov, Simon Brett and the funniest man of all, Mike Sadler (who, sadly, gave up comedy for academic life in Glasgow and France). We were, looking back, on the cusp of change, for while the wonderful world of 1960s Britain – the Beatles, the satire boom, mini-skirts and all the rest – was opening up, the more conservative world we had left behind lingered on in Magdalen, where you could still find tweedy men with double-barrelled names hoping to follow in their father’s footsteps as military officers. But it was live and let live and in summer the incomparably beautiful college would resemble an upper-middle-class holiday camp.

Most of John’s sketches were written with Michael and another close friend, Walter Merricks. Walter was actually at Trinity College but spent so much time in Magdalen that we regarded him as one of our own. Together, these three put together endless satirical sketches. Michael’s speech impediment prevented him from acting – sadly for those of us who knew him for his punch lines often gained considerably by being placed at the end of a long stammering sentence which built tension the longer it lasted. Walter, a gentle, Ian Carmichael-like character, often played alongside John. The three of them were pretty much inseparable and to share lunch with them meant sharing in a constant stream of jokes and impersonations. John was fascinated by the rise of Harold Wilson – whom he could impersonate quite as well as John Bird later did – and the way Wilson sought to exude an image of tough intellectualism (‘the white heat of the technological revolution’) while also being the down-to-earth Huddersfield man in a Gannex raincoat. ‘Labour has some of the best minds working on the gritty realities of our time,’ John’s Wilson would say: ‘Nothing could be grittier. And let me tell you, each of these men has a mind like a steel trap.’ Another scene had John standing in Gannex raincoat in Downing Street in the rain: ‘As you can see, I’m getting wet. But Labour believes in equal shares for all. In the new Socialist Britain we shall all get wet.’

But the famous Beyond the Fringe sketch about Macmillan (‘I have been travelling abroad on your behalf and at your expense. I spoke to President Kennedy of Britain’s role as an honest broker. He said no one could be more honest, while I agreed that no one could be broker’) was hugely influential and there was much mocking of upper-class types, generally called Carruthers. Often, Walter played Carruthers – he took to it like a natural. In one sketch John, then playing Carruthers, said ‘But you are speaking of the woman I love. I always carry her picture with me,’ slowly taking out of his pocket a £5 note and staring passionately at the portrait of the Queen. John was also fascinated by the techniques and lore of stage humour. There was much talk about ‘the boffo’. Comedians, he would explain, rated jokes. Some merely produced a smile. A step up was the titter, followed by the genuine laugh. This was followed by the deep belly-laugh, denoting really serious amusement (John would imitate each of these stages). But then came the boffo. What exactly, we’d ask, was the boffo? ‘The boffo,’ John would answer, looking grave, ‘is the joke that kills.’

from Chapter Four

Exploring the Secret Garden

A great deal of Magdalen’s history was, indeed, frankly disgraceful. (The impish historian, A. J. P. (Alan) Taylor, still a great figure in the college when I arrived, also liked to emphasise that examination of the college’s principal benefactors served merely to prove that, far from crime never paying, pay it almost invariably did. He explained this in a lecture given at the speech day of Magdalen College School in Wainfleet, Lincolnshire. He was, he told me, never invited back again.) The college’s ‘long 18th century’ was prolonged by the reactionary and 63-year long presidency of Martin Routh who signalled his attachment to the past by wearing an 18th-century wig and knee-breeches until his death in 1854. He insisted on taking a coach and horse to London and, when told by undergraduates that the train was far quicker, angrily retorted that he did not wish to know that. Under Routh the college not merely vegetated, but almost died. By the 1830s it was down to only a dozen undergraduates or so and absenteeism among the Fellows was so chronic that even during term two-thirds were missing. Ultimately the government lost patience with Oxford and legislated reform. At last more modern subjects were introduced, and two more government commissions followed. Oxford has ever since lived in fear of a further royal commission.

In the new era Magdalen was headed by President Herbert Warren, a man bursting with all the energy, self-belief and ambition of the imperial Victorians. Warren was also a hearty and a snob who did all he could to recruit aristocrats and muscular Christians. Chief among his prize captures were the imperial prince of Japan, Prince Chichibu, and later the Prince of Wales (known among the undergraduates as ‘the Pragger Wagger’). Warren asked Chichibu what his name meant and when told that it meant ‘the son of god’ replied that ‘you will find that at Magdalen we have the sons of many famous men’ – though some believe that this story really relates to the son of the Indian guru, Krishnamurti. But the college remained idle and undistinguished. The history book shows that in 1872 Magdalen’s dons were noted for their ‘sovereign immobility’ while one Harrovian was described in 1901 as ‘doing nothing with utmost steadiness’. But it was not unusual. The young John Betjeman, who was sent down from Magdalen, wrote of how ‘life was luncheons, luncheons, all the way’. P. G. Wodehouse naturally decided that Bertie Wooster had been to Magdalen.

It was only in the late 19th century that Magdalen began to have a few international scholars of note. On the undergraduate side Oscar Wilde was one of the few to earn academic distinction, though inevitably he satirised Warren’s muscular Christianity. It was a typical Wildean joke that he should invite Warren to lunch to meet a friend of his, then writing an interesting book – Bram Stoker, author of Dracula. Wilde said that Oxford was ‘the most beautiful thing in England’ and had no praises too high for Magdalen. But the fact remained that Wilde’s brilliant academic achievements were without parallel and there is little to suggest that most students even attempted much study.

Magdalen students were always seen as stand-offish – partly because of the personal independence bred of spaciousness but also because the college attracted a rather aloof aristocratic clientele. With the coming of the automobile the line of Rolls, Bentleys and Bugattis outside the Lodge at the beginning of term was unmistakeable and somewhat intimidating. But Magdalen is also a separate little republic, a medieval village of its own on the edge of the old city. Its grounds are so extensive that you can walk as far as you want without leaving the college – it has a magnificent circular walk named after the essayist Addison, a past Fellow – and since its playing fields are immediately adjacent you can also play any sport while remaining inside it. You can even go punting on the river without leaving the college. All of which makes it easy to live a self-contained – and often very full and amusing – social life without stepping out beyond the college walls. In the 1960s Cherwell used to poll final-year undergraduates about their choice of college. Virtually everyone replied that they would again choose the college they’d been to. But the follow-up question was the real one: if you were not to go to the same college again, where would you choose to go? Magdalen would win this by a country mile.

Real change only came to Magdalen in the 1920s and 1930s, when a phalanx of extremely powerful intellectuals became Fellows and demanded higher standards and greater meritocracy. This movement for reform was led by Harry Weldon who made sure that his own subject, PPE (Politics, Philosophy and Economics), was a bastion of such values. Weldon met considerable opposition, notably from the English tutor, C. S. Lewis, who regarded him as the devil incarnate.

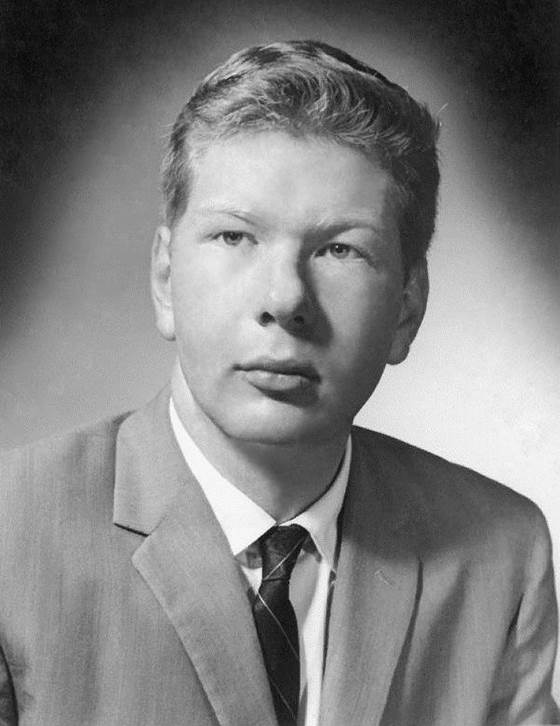

Harry Weldon came to Magdalen on a scholarship from a relatively modest background but the First World War intervened and in September 1915 he was commissioned in the Royal Field Artillery and spent the war in France, finishing as an acting Captain and with a Military Cross and Bar. Those familiar with the mores of the British Army will recognise that this meant that he was quite insanely brave and clearly on the verge of a Victoria Cross. He went up to Oxford finally in 1919,  took a First Class degree in 1921 and almost immediately became a tutor at Magdalen, remaining there – a bachelor living in college – for the rest of his life. During the Second World War he became assistant to Sir Arthur Harris, head of Bomber Command (a role later celebrated in film), which meant that Weldon had to use his logician’s skills (he wrote a book on Kant’s logic) to defend the strategic-bomber offensive (i.e. saturation area bombing) to Cabinet sceptics such as Stafford Cripps. It is doubtful that the moral problems associated with this ever quite left him: in later years he would startle some of his students by asking questions such as ‘How many lives is Cologne cathedral worth?’

took a First Class degree in 1921 and almost immediately became a tutor at Magdalen, remaining there – a bachelor living in college – for the rest of his life. During the Second World War he became assistant to Sir Arthur Harris, head of Bomber Command (a role later celebrated in film), which meant that Weldon had to use his logician’s skills (he wrote a book on Kant’s logic) to defend the strategic-bomber offensive (i.e. saturation area bombing) to Cabinet sceptics such as Stafford Cripps. It is doubtful that the moral problems associated with this ever quite left him: in later years he would startle some of his students by asking questions such as ‘How many lives is Cologne cathedral worth?’

Plate 2 (left ) Harry Weldon. Acerbic, analytical, slightly military. Peters and Waterman argued in In Search of Excellence (1982) that Magdalen was the most excellent college in Oxford. Weldon (1896–1958) was the man who made it so. (Magdalen College Archive )

Weldon’s war was clearly remarkable. The headquarters of RAF Bomber Command were in the village of Walter’s Ash, just outside High Wycombe. This could easily be reached by a half-hour car ride from Oxford and it would seem that Weldon spent the war commuting between his rooms in Magdalen and Walter’s Ash. The contrast must have been surreal. Oxford was never bombed (there were always rumours of a secret deal whereby Nuremburg was never bombed in return) and Magdalen, though more than half empty, would have remained as beautiful and peaceful as ever. At Bomber Command HQ desperate plans were always afoot to bomb the invasion barges, the Tirpitz or German cities, to launch the Dam Busters’ raid, to build a special ten-ton blockbuster bomb and so on. It must have been an extraordinary daily experience for Weldon to wake amidst the beauties of Magdalen, hasten down the A40 to the tense epicentre of the war effort where often horrific decisions had to be faced and then return to the complete calm of Magdalen for dinner at High Table and a hand of bridge with the other Fellows still left in the college.

Although Weldon was open and friendly with all his students no one doubted that he was a man of steel who, in both wars, had had to face appalling situations and ultimate questions. He smoked incessantly, using an ivory-and-silver cigarette holder more appropriate to the silent-movie era and his students, though devoted to him, were never quite sure what to expect from him. Anthony King remembers asking him earnestly whether he had ever read Bertrand Russell’s Why I am Not a Christian and getting the answer ‘Who the hell cares why Bertie isn’t a Christian?’ Although he was always jovial, his habit of asking unanswerable questions suggested a deeper, brooding awareness. Some suspected that this superficial geniality masked a deep melancholy. C. S. Lewis said of him that ‘He believes that he has seen through everything and lives at rock bottom.’ Magdalen was his life and its fraternity all the family he had. His death at 62 from a cerebral haemorrhage was perhaps a mercy because he remained in harness to the end.

Although Weldon was open and friendly with all his students no one doubted that he was a man of steel who, in both wars, had had to face appalling situations and ultimate questions. He smoked incessantly, using an ivory-and-silver cigarette holder more appropriate to the silent-movie era and his students, though devoted to him, were never quite sure what to expect from him. Anthony King remembers asking him earnestly whether he had ever read Bertrand Russell’s Why I am Not a Christian and getting the answer ‘Who the hell cares why Bertie isn’t a Christian?’ Although he was always jovial, his habit of asking unanswerable questions suggested a deeper, brooding awareness. Some suspected that this superficial geniality masked a deep melancholy. C. S. Lewis said of him that ‘He believes that he has seen through everything and lives at rock bottom.’ Magdalen was his life and its fraternity all the family he had. His death at 62 from a cerebral haemorrhage was perhaps a mercy because he remained in harness to the end.

Plate 2a (left ) The cover of the 1960 reprint of Weldon’s popular Pelican The Vocabulary of Politics (1953) (Cover design by Alan Fletcher)

Lewis’s career was remarkably similar – he was wounded on the Somme and was a Fellow of the college from 1925 to 1954, when he departed for a chair in Cambridge. Both men lived as bachelors in rooms in college and both kept barrels of beer there so as to entertain undergraduates. But whereas Lewis was a passionate Christian and conservative, Weldon was an anti-clerical Freemason and radical. Bachelors living in college not only had the time for strong involvement in college affairs and political intrigue but often also an inclination towards it, for the college was their world. Both men could have a cutting tongue but they were polar opposites. Weldon was caustic about all forms of organised religion and was well known for his way of sharply attacking first-year undergraduates for their conventional and religious beliefs. When they too had all become radicals he would turn on them in second year and argue scornfully against their new beliefs, mercilessly exposing the holes in them. By the end the students were left not being sure what they believed about anything but, sharpened by this brutal experience of Socratic dialogue, would find themselves in a state of free-floating agnostic cleverness. Weldon did the same to their political and economic views. Naturally, Lewis saw this deliberate undermining of belief as, quite literally, the work of the devil. Indeed, when he became Vice-President, Lewis inherited the Vice-President’s book in which all holders of that office are expected to write down a completely unvarnished account of the real life of the college. Only later Vice-Presidents are allowed to read this. Lewis, during his Vice-Presidency, wrote a play in the book in which the figure of the Devil is quite clearly modelled on Harry Weldon. This remains the one great piece of unpublished fiction by C. S. Lewis.

In the struggles fought by these two men over 30 years Weldon generally got his way. The President’s power over undergraduate admissions was sharply cut back, the power of the old school tie curtailed and merit and achievement exalted in its place. The college began to produce more Firsts and has ended up with (currently) nine Nobel Prize winners. This reform movement merely strengthened after 1945. Most Fellows were on the Left and determined to eliminate all trace of Magdalen’s Brideshead image. By the 1950s Magdalen was quite commonly near or at the top of the Norrington results table, which was why students blithely assumed that the college had been a pillar of academic excellence for centuries past. Although it continued to attract an unusual variety of people from Wilfred Thesiger to Andrew Lloyd-Webber, it was as likely to be known for the radicalism of its Fellows as anything else: A. J. P. Taylor was better known nationally as a leader of CND.